|

How Blessed I Am

In 1980, I began a year of life in the small city of Sydney, Nova Scotia on

beautiful Cape Breton Island, home of the Cabot Trail. Sydney was a dirty steel town.

The mill was fed by the multitude of coal mines surrounding the area.

Coal, first discovered in the 1600's, was a means of support for centuries in

the area.

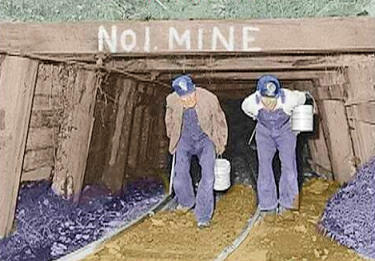

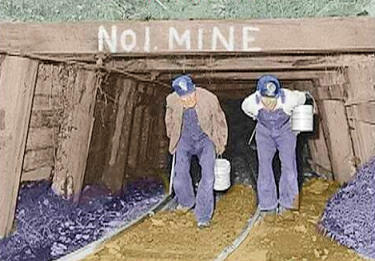

The majority of residents either worked in the steel mill or under the ground. I

became fascinated by the mines, the miners and the life they led. One weekend, I took a

drive to Glace Bay, a neighboring city, to visit the Miner's Museum. I toured the main

floor, where they depicted the history of coal mining in the area. Pictures of men, faces

black with coal dust, hung from the walls. Many would die from black lung disease long

before old age took them home to glory.

The museum was built over an exhausted mine. I mingled with tourists from

around the world. We waited in front of an elevator, as a guide handed out helmets

with lights and heavy miner's coats.

The guide checked us over, smiled his approval, and opened the door to the

elevator. We crowded in. The doors silently closed. We smiled nervously at each other.

The mine was shallow. A few moments later, we stopped, the doors opened and the guide

led us into the tunnel.

"Watch your heads!" he warned. "The ceilings are low." We followed him down

the tunnel. It was lighted with electric lights then, but while in production, the tunnel was

as dark as the walls of coal above, beside and under us.

We walked hunched over, so as not to hit our heads. Along the way we paused to

look at the displays of mining equipment from centuries long gone. At one lighted alcove,

sat a wicker cage. A canary once perched inside. Loved tenderly by the miners, it was

well fed. It sat and waited to give its life as a warning of the deadly methane gas the coal

produced. Undetectable to the miners, methane buildup would kill them or explode with a

force strong enough to collapse the tunnels they worked. The canary's death, like a

smoke detector, warned the men of danger.

My interest wasn't satisfied. I needed to know more. Across the harbor from

Sydney, in the town of Sydney Mines, another tour waited.

Once again, I was the only local in the group of tourists. We dressed in miner's

clothes, climbed into the coal cars that once lowered the miners under the ground. The

guide asked us turn on our helmet lights. There would be no lighting on this tour. We'd

get the full experience.

A motor attached to a pulley roared to life. Our cars jerked and began the descent

into the dark mouth of the tunnel. Suspended by what was then the longest single length

of steel cable in the world, we rolled down the throat of the mine. We'd traveled more

than a mile through the tunnel and were under the harbor before we stopped and climbed

from our coal cars.

Our helmet lights flashed across the walls of the mine like a swarm of dyslexic

lighthouse beams. The tour guide pointed to fossils of plants in the ceiling and walls. It

was a history lesson of earth's early beginnings.

"Turn off your helmet lights!" the guide ordered. "I want you to experience the

life of a miner."

One-by-one we turned off our lights until there was just the single beam from the

guide's helmet, and then it too went out. The darkness was total - so thick, you thought

the very air itself had been sucked out of the mine. And the silence! The silence was

complete except for the breathe of fear from my companions. Somewhere, water dripped,

where the harbor seeped through seams in the rock and coal above us.

"The miners experienced this everyday. This was their life. You can turn your

lights on now." There was a sigh of relief.

We climbed back into the coal cars and were pulled to the surface. The warm sun

had new meaning to us.

Back in my small rented room in the basement of my landlord's house, I closed

the blinds and turned off the lights. I contemplated a miner's life: under the ground, black

dust, no sunshine and much danger. It's not a life I'd wish on anyone.

Many people hate their jobs. There have been a few I didn't like. I whined. Then

I thought about the coal miners and realized how blessed I am.

~ Michael T. Smith ~

<heartsandhumor@gmail.com>

Michael lives in Ohio with his wife Ginny and his stepdaughter's

family. You can see a list of Mike's stories here:

http://tinyurl.com/moud8u And you can get his stories emailed to you

by signing up here: http://tinyurl.com/ldjruh

Let Michael know what you think of his story:

Michael T. Smith

[ by: Michael T. Smith

Copyright © 2010, ( heartsandhumor@gmail.com ) -- {used with permission} ]

Inspirational Stories

SkyWriting.Net

All Rights Reserved.

|